A Day in North America’s Oldest Theatre

The pants come first. It makes sense. Once the street slacks are off and the pressed blacks are on, you can see yourself in the role. The shirt is pleated vertically, seven folds on either side like pairs of cloth ribs. White plastic buttons run the middle though some are black beaded. The cummerbund has its origin in the early 17th century. It’s Hindustani and Persian, meaning loin band or waist band. A fellow usher told me this and I listened intently, in part because he was a friend, in part because he stood in silence for a living and could finally speak. Jacket. Shoes. Bow-tie. That’s it. Now don’t forget to swallow the gum.

Ushers are a mishmash of security guard, customer service rep and penguin, employed to conduct patrons to their seats. They may watch the performance in the shadows but must be ready to assist, to shine their four-dollar flashlights for anyone not born with night vision. They should guide the elderly with an arm or their entire body weight and politely refuse the admittance of noisy snacks. Bottled water is waved into the house like an old friend. Booze and booze-fueled tomfoolery is not.

Being employed at the Royal Alexandra Theatre, you can’t help but feel the hundred years of star power at your back. As the longest continuously running theatre in North America, this Toronto playhouse and national historic site has made a living from letting its guests walk all over her. Three thousand productions have played out under the proscenium over the years, including Jane Eyre, Billy Bishop Goes to War, Hair, Crazy For You, and Mamma Mia. Just as impressive are its performers: John Gielgud, Fred Astaire, Humphrey Bogart, Mary Pickford, Orson Welles, Al Jolson, Martin Short, Edith Piaf, Maggie Smith, the Barrymores minus Drew and hundreds more without sidewalk stars. Occasionally a household name will arrive as a patron, though they’re nothing to be afraid of. They’re prone to tardiness like everyone else and ooh and ahh pretty much on cue. It’s the building that has the closest connection to pomp, or more precisely, royalty. The Royal Alexandra (the Alex) takes its name from the former Danish princess and great-grandmother to QEII, Queen Alexandra. She was Queen Consort to Britain’s Edward VII, a title given to the wife of the reigning king. It was Edward who authorized the use of the name. But back to the grunts.

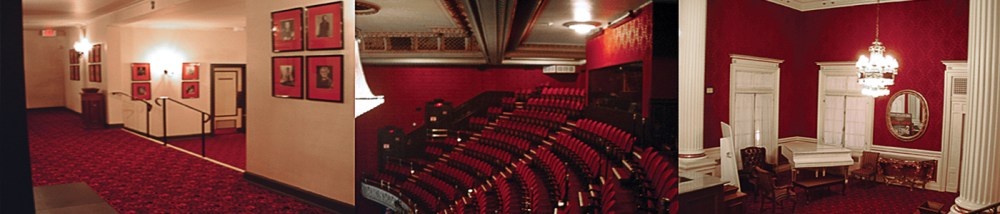

By 6:30 p.m. they’re punched in via hand-scan and suit up, check their assigned positions and stuff. Stuffing is a robotic duty, the process of inserting brochures and notices of cast changes into the production programs. The underbelly of the Alex is where it’s done, either jammed into the unfinished set-piece ushers call the staff room or in the plush red velvet interior of the basement lounge. What’ll it be, chipped paint and water stains or red velvet and whiskey? The lounge, officially known as the Yale Simpson Room, was named after owner Ed Mirvish’s childhood friend and former Alex manager. Formerly though, it was the site of an ice pit which served as the theatre’s air conditioner. No one complains about working underground. Toronto walks over their heads but not with this much class. Probably the wrong word. For every glamourous impression, there’s another, like ushers guzzling free coffee, wondering why their dress pants haven’t come back from the cleaners.

A patron is a citizen but they’re also travellers who arrive, have an experience and then leave. Before entering that experience however, there is protocol. A set of heavy double doors with brass fittings sit just in from the overbulbed marquee. The outer lobby is next, with dual box-office windows and helpful heads within. The space is enclosed but unheated, a more important detail during a cold Toronto winter. Cracking the inner doors to allow a patron to cross the threshold before the appointed hour is touchy. If you’re frail enough, if your lips are blue enough, it’ll be considered. Otherwise, there’s a process to the night. Outer lobby to inner, inner lobby to house, house to rising curtain. Nothing is revealed before it should be. They’ll have to wait to taste the fruits of Belfast-born architect John M. Lyle’s efforts, to see the imported marble, the sculpted walnut and cherry wood, the staircases that creak nicely on impact and crystal chandeliers which could use a dusting but still they’re marvelous.

Lobby doors open at 7. Three ushers give patrons the needed information as they rip tickets. “You’ll be going up to first balcony. The doors will open at 7:30 but until then we have a bar and lounge upstairs, washrooms as well.” It’s a mouthful but appreciated and hopefully diffuses the temptation to jump the gun. Even an usher grown tired of process will pounce when a patron attempts to sneak a peak ahead of schedule. “I’m sorry sir, but the house doesn’t open for another eight minutes.” For some it’s overkill, this militant effort to protect the world of make-believe, but it is necessary. Before the appointed hour, final sound checks are underway and a performer may happen to be on stage, fine-tuning that tricky slidy-spinny thing one last time. And yes, to protect the world of make-believe.

Seven-thirty. You have the house. The innermost doors are cracked and ticketholders poor in like syrup through a dollhouse. By and large, the syrup is quite friendly and as patrons are expected to do, they ask questions. “How many times have you seen Mamma Mia?” About 300. “Are you an actor too?” Not really. There are even predictable favorites. The upper balcony receives the brunt of them for two related reasons: its height and the number of steps it takes to get there. In the spirit of the 19th century theatre, the Alex has no elevators, and the walk can take a toll. “Whew! I hope you have oxygen.” “I need to get into shape.” “Has anyone ever fallen?” To the first and third the answer is yes, though few ushers will actually give dirt on number three. A response to the second is better served with a chuckle that doesn’t address proportions.

Orchestra. Working on the main level has its demands. The degree of customer service increases by the sheer number of seats present. Rows are lettered AA to V from front to back, with most having between 26 and 35 seats. A pair of curtained boxes are nudged into each corner flanking the stage, likewise on First Balcony. Six ushers take positions spread evenly across the back of theatre, two in the corners of the far aisles, two at the heads of the two main aisles and one facing the beautiful people as they enter. To see on this level is to be seen. There are jeans, t-shirts even, but not many. Most impress. Orchestra too generally contains the best view of the action. The Alex is one of Toronto’s original steel-framed structures, more of a big deal considering its internal impact. It contains cantilevered balconies, eliminating the need for support pillars. This ensures clear visibility and a sense of openness.

In respect to great views, the first few rows of First Balcony (the dress circle or mezzanine) could give Orchestra a run for its money. A21 is the center seat in the front row, said by many to be the best seat in the house. It’s also known by the moniker The Princess Seat, after Princess Diana who sat there during a 1991 showing of Les Miserables. It’s a piece of theater trivia patrons seem to enjoy. Upper Balcony, however, is unique to the extent that it sacrifices comfort and safety for cost. Leg room is a fantasy and the chairs no more than thin cloth wrapped around a wooden base. In terms of a seating blueprint, it’s similar to its two sister levels below but with a caveat that would throw Hitchcock an epileptic fit. The seating is steeply angled downward. “God, I can’t do this! I don’t think I can do this.” An usher might not tell a patron at this point that there are no refunds. Better to use therapeutic assurances and guage the results. “There are poles here along the steps to guide you. And if you like I can walk down in front of you.” The odd customer will jiggle a foot over the top step like they’re testing water temperature, but with continued refusal there are rarely more than three options: locating a seat with a similar price point, a paid upgrade or, in the event of a full house, a very underwhelming monitor in the First Balcony lounge.

What the third level does give is an unobstructed view of “Venus and Attendants Discover the Sleeping Adonis,” the ceiling mural by Canadian artist Frederick S. Challenger. And something else. Hands down “the paupers,” as Dame Edna refers to Upper Balcony patrons, have more fun. Maybe it comes from the feeling of being out of the loop. Sitting in the rafters isn’t exactly an intimate experience after all, but even at the risk of tumbling out of their seats, Upper Balcony patrons will stand and cheer. And snap pictures. The photography issue can be an issue. The theatre has a strict no video/no camera policy. Any technology with more memory recall than a sketch pad and you’ll be kindly asked to stop. The reasons for the policy are well known: copyright laws and artistic propriety. For an actor on stage though, it could be a scene-stumbling distraction, say nothing for a dancer.

The Alex was brought into the world by 21-year-old foundry owner Cawtha Mulock, “the boy millionaire,” as he was known in the local press. Aside from a taste for business and investment, he wanted to put Toronto on the cultural map. It opened its doors in 1907 as a touring theatre. Over the years the theatre saw its share of real-life drama, from its rivalry with the New York based Theatrical Syndicate to its purchase, restoration and eventual triumph courtesy of Toronto entrepreneur Ed Mirvish. Mirvish had already made a name for himself with his no-frills discount store Honest Ed’s when he rescued the Alex from possible demolition in 1963. His formula for success was simple: scout out hit musicals from the stages of London and New York and run them with Canadian casts. Later he began producing his own plays for the theatre. Ed Mirvish passed away in July of 2007 at the age of 92. His son David runs the Alex and its younger cousin The Princess of Wales through Mirvish Productions.

Eight sharp. The lights dim. Once you know a production by heart, you look for other things to do. Some ushers read. Others pace or scratch in a notebook. There’s something too to people watching, examining the faces of fifteen-hundred guests, each uniquely reflecting stage light. They react as a group mostly, laughing, reminiscing, on occasion yawning. “See, there’s this theory about the nature of tragedy, that Aristotle didn’t mean catharsis for the audience but a purgation of emotions for the actors themselves. The audience is just a witness to the event taking place on stage.” Fine words coming from Jim Morrison, The Doors frontman who usually was the one on stage. But where does that leave the usher, the one watching the witness, the one who sells them Haagen Dazs during intermission? No point in overthinking it, the job. Not that there isn’t the slightest charge when that bow-tie snaps into place. It is show business after all.

August 2007 marked the 100th anniversary of the Royal Alexandra.

Photographs by Judy Sara