When it runs out, you can feel your breath suck in. Even from a distance there’s no getting around it, this is a big piece of meat. It bounds out of the gate like it’s been held back for a lifetime and let go. Three toreros, banderilleros, are waiting on the field, though don’t let the wide magenta capes fool you. They’re closer to assistants. Only the matador will get celebrity billing on the poster and perform the graceful close-quarters maneuvers known as “the dance with death.” Every story needs a hero.

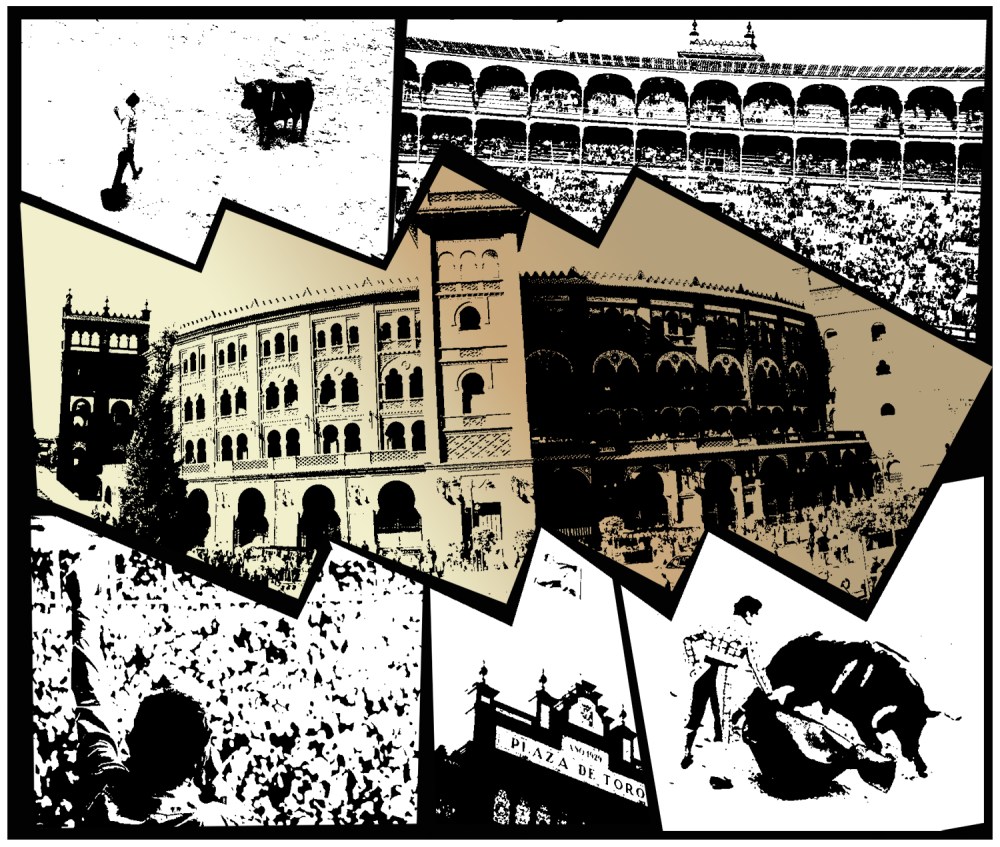

In Spain, the rhythm of life takes its cues from time and temperature. As anyone living above the 49th parallel can tell you, it’s more challenging to celebrate life when the mercury drops. It’s less of an issue in Madrid, the mountain edged capital where sidewalk patios and ornamental fountains offer some relief to the hot, dry summers. From March to October, it’s arguably the ground zero of bullfighting. La Plaza de Toros de Las Ventas is where it happens, and has been since 1931. The outer face of the arena is tinted like perfectly toasted bread. Its ornamental brickwork and horseshoe arches reveal Muslim tastes, an architectural style known as mudejar. From fashion to cuisine, it’s just another example of the country’s varied heritage. The world turns primitive as you enter, surrounded by ceramic tile and cold stone. Red musty cushions can be rented for a euro, but roughing it has a certain gruff coolness about it. It is a blood-sport after all, and one with multiple roots.

The peninsula’s relationship with the bull has evolved as it has for the better part of 2,000 years. When the Moors overran southern Spain in the early 8th century, bullfighting had already existed care of the Visigoths, though it was hardly refined or ritualized. Moorish influence added the element of attack on horseback, but it was the Bourbon King Philip V who would bring the event to the ground. He didn’t see bullfighting and the aristocracy’s involvement as a reputable mix, and prohibited them from taking part. The commoners took over. The infamous red muleta used in the finale, and the estoque (sword) was introduced by Francisco Romero in the 1720s, more or less completing the classical Spanish form. For a first experience though, one might prefer being out of the know. Naivete has a way of raising the bar until you’re either satisfied or disappointed.

The siesta or mid-day break, reputed to be waning in recent years, seems to be thriving here at least. When the corner bars and cervecerias fill up, you’ll wonder how productive the day’s second half can be if heads are still buzzing. Either way, lust for life is at once a fever that Spaniards seem to have a knack for and a stereotype every outsider wants in on. Far be it for bullfighting fans to disagree. When aficionados speak of la corrida, or the bullfight, they speak of a tradition tied to the human condition. Words like life, death, desperation, valor, success, and despair are used proudly in their explanations. Even its structure bears relation to drama. The performance is sectioned into tercios (thirds), acts the matador uses to size up his opponent in strength, movement, and mood. He’ll begin in the tercio de varas. The picadores (lancers) enter on horseback soon after. A willing bull will charge. It slams into the padded horse and attempts to lift it from underneath. This gives the picador time to lance the bulky neck and shoulder muscles of the animal, weakening and lowering its head for the final kill. The tercio de banderillas follows. Capeless banderilleros run at the bull head on, piercing its flanks with colorful barbed rods called banderillas. The tercio de muerte completes the action. Here the matador does his thing, engaging the bull in a series of passes (faena) to show his mastery over the beast before impaling it through the heart. Such is the melodrama, the struggle of man in ritual form.

The matador (literally “killer”) is in the thick of it, fully conscious of the outcome, perhaps half conscious of the bull’s ear he might be honored with for a clean victory. Tauromachy’s top ringmasters are hailed for their courage and poise under pressure, but also their respect for their opponent. Ernest Hemingway certainly saw it, and often wrote it down, explaining the ritual behind the apparent barbarism and the reverence behind the ritual in his work, “Death in the Afternoon.” A line from “The Old Man and Sea,” sums it just as well. “Fish, I love you and respect you very much. But I will kill you dead before this day ends.” In recent years though, accusations of grandstanding, of playing to the crowd and away from matters of the ring seem that much louder. Fingers point to modern media. It has given many matadors pop-star status and the tabloid coverage that rides with it, but idolization is nothing new. Manolete, a heavyweight known for his poker-faced approach to the sport, was fatally gored after a return from retirement in the late 40s. Then head of state Francisco Franco allowed three days of national mourning.

Spain is often noted for being of two minds. To an outsider, it appears as homogeneous as its travel brochures. Paella and flamenco. Cervantes and Almodovar. They’re all part of an imagined tableau entitled, “This is Spain.” But there’s another side. Christians and Moors. Republicans and Nationalists. History has a way of coloring the dichotomy in shades that Frank Capra would admire. In “The Ghosts of Spain,” Guardian journalist and writer Giles Tremlett remarks, “the pain and joy, pena and alegria, are the two emotional motors of flamenco.” It’s an idea that might as accurately be applied to bullfighting. Arguments for and against have been raging for centuries. Pope Pious V disallowed the combat in the 16th century, though it was overturned less then a decade later. Franco openly encouraged the sport. Recent signs indicate the tide is turning once again, this time for the bull. State-run broadcaster TVE has censored itself from showing live bullfights in a move to protect younger viewers. The National Association of Bullfight Organizers reacted accordingly, calling it “a shameless unjust attack on culture.” You can’t please everyone. Then how about the majority? Take the northern autonomous region of Catalonia. In 2004, city counselors in the capital of Barcelona voted to make the city “anti-bullfighting.” Opinion polls favored the abolition at 70%. No law has been authorized by Parliament as yet but the effects have stung. Rings throughout the region are gradually closing up shop, or being converted to less contested forms of entertainment, shopping and musical events. It could be foretelling given the area’s ability to set cultural trends in other areas though Catalonia is just as well known for its own brand of nationalism as its stance on animal cruelty. The question some are asking is whether it even matters.

Las Ventas. Even in a foreign language, a crowd sounds like a crowd. Inside, retirees in navy-blue captain’s hats elbow their neighbors, commenting on the action below. Plastic cups of draught are raised and fired back while others turn and gawk like obvious first timers. One greying, pot-bellied corrida fan wrapped in a checkered vest waves to a friend in the tiers above as something made of brass blares. Consider it the next-act buzzer, just another part of this time machine. Aside from the designer handbags and roll-on deodorant, this is one afternoon that still holds claim to being 21st century free.